Meticulously designed, tenderly acted, and sensationally scary, it lingers.

The Orphanage (El orfanato) is the 21st-century’s preeminent ghost story. That’s high praise, yes. But even fifteen years after release, the enduring impact of J.A Bayona’s gothic opus remains unmatched. Rooted in the gothic tradition of contextual ghosts—ghosts indicative of tragedy and sin, longing and love—Bayona’s haunted house masterpiece consistently subverts expectations, bobbing and swaying to a classic rhythm rendered new again. The ghosts of The Orphanage matter, existing in the periphery and center screen as more than vessels for quick scares and ephemeral jolts. They’re tactile players with stakes to match the protagonists’. With an emphasis on character and grounded scares that never strain credulity, the kind that would later imbue all ostensible elevated horror, The Orphanage was a decade ahead of its time. It’s a ghost story in the tradition of Henry James that threatens to terrify and break hearts in equal measure.

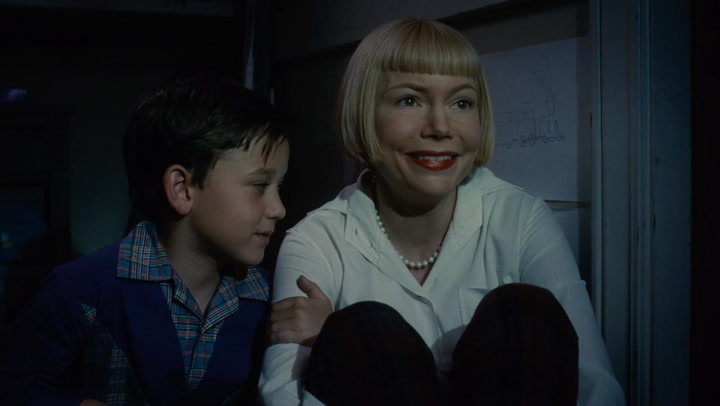

The central conceit is simple. Laura García Rodríguez (a mesmerizing Belén Rueda, Goya nominated for her work here) purchases the coastal orphanage she grew up in. She moves in alongside her husband, Carlos (Fernando Cayo), and son, Simón (Roger Príncep). She plans to reopen it as a home for children with special needs. Immediately, Bayona works wonders reinterpreting old tropes for a new generation. The wistful, fantastical musings of producer Guillermo del Toro color every character beat. Meticulously designed, every pounding on the door or glimpse of something else in the house serves considerable narrative purpose. The mise-en-scene is terrifically supernaturally arranged. Small elements of the narrative serve as throughlines that unfurl throughout, leading to an ending that’s both profoundly curative and heartbreaking.

Also Read: Nightmare Alley’ Review: Guillermo del Toro Delivers A Startling, Frostbitten Spook Show

The crux of The Orphanage is Simón’s disappearance on the day of a garden party for the new facility. This disappearance coincides with the appearance of Tomás (Óscar Casas), a deformed boy wearing a sack who lived at the orphanage alongside Laura. Bayona’s ghosts matter, but the innate restraint in rendering them three-dimensional might frustrate some contemporary audiences. The Orphanage is terrifying, though not in the visceral vein of The Conjuring. Yet, the abounding poignancy remains inimitably effective. The titular setting is a gravity well for trauma and suffering. Laura’s benevolent perspective is the key unwrapping the ongoing hauntings. Before the Bent-Neck Lady and a lineage of elevated specters, there was Tomás, a ghost not looking to haunt, but to simply communicate.

The considerable emotional impact of The Orphanage cannot be understated. It’s a hoarse, gravel-trailed cry from the beyond, a serrated knife to the heart that cuts deeper and deeper as it progresses. It spills everything from within and rearranges it as something new, something thoroughly and painfully empathetic. It identifies the ghosts in the audiences’ lives and manifests them unlike any movie has done before while still remaining commercially and critically accessible. The central mystery is compelling, and Bayona even throws in a few flashes of grisly gore to elevate the stakes. Trauma and suffering are ugly, generational affairs, and they’re rendered beautifully with the swiftness of a broken, bloodied jaw.

Also Read: Zena’s Period Blood: Returning to THE ORPHANAGE

Laura, in the dénouement, visits the world of the dead. She overdoses on sleeping pills, having been instructed that those close to death can more easily pick up on the messages of the dead. Once there, she discovers what happened to Simón. On the day of the garden party, he demanded Laura see his friend Tomás’ house. She refused, but he went anyway, through a hidden door in a hallway closet. While looking for him, Laura moved construction scaffolding and it fell within the closet, blocking the door and trapping Simón inside. The pounding she heard that night wasn’t ghosts. It was Simón begging to get out. The final crash she heard wasn’t supernatural. It was Simón falling through the railing and breaking his neck.

For months, she searched for a missing son, not knowing he was at any given moment a few paces away, in a secret room behind a secret door where the orphanage kept all its ugly, sinful things locked away. The apparitions she saw weren’t looking to hurt her. Instead, they were trying to guide her. Guide her to where her son had been the entire time, now simply a decaying husk. It’s a graphic shot, the sight of a battered, almost desiccated Simón alone on the basement floor, and it stings more than most any ghostly climax to come before or since.

Also Read: ‘Hellboy 3’: Ron Perlman Says We Deserve The Third Guillermo Del Toro Chapter

J.A. Bayona, like the practitioners that came before him, is a master of psychological ghost stories. He understands the chasm between the mind and the tangible world, the dark, creeping areas where ghosts most often manifest. Not quite fantastic or supernatural, though not quite real. Conceived in pain and having died in tragedy, they’re sorrowful figures, exhibitions of human suffering and regret. The tagline for The Orphanage reads “A love tale. A horror story” and unlike most exaggerated taglines, it’s true. It’s about the love between a mother and son, a woman and her friends, and the love that unites and binds us all. It’s a simple human truth wrapped in a masterpiece of gothic flourishes and sensational scares. The Orphanage, like the ghosts at its core, will linger for years.

![Shane Hawkins Drums with Foo Fighters at Taylor Hawkins Tribute Concert [Video] Shane Hawkins Drums with Foo Fighters at Taylor Hawkins Tribute Concert [Video]](https://consequence.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Shane-Hawkins-and-Violet-Grohl.jpeg?quality=80)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/23/805/n/1922564/3c7878ba67193e463ea470.81388103_.png)