Eun-Kyung Yoon’s The Tenants reflects South Korean hardships that are universally traumatic. It’s fringe horror, nodding to existential absurdism and black-and-white interpretations of Kafkaesque illusions, but terrifying nonetheless. Yoon examines the drab reality of middle-class workers who only exist to uphold any city’s ecosystem: corrupt capitalism built on the backs of its forgotten contributors. Storytelling doesn’t lack eerie imagery of crawlspace dwellers or sleep paralysis encounters, yet Yoon avoids traditional genre formulas. Don’t expect the shared-space suspense of Two Pigeons or the cuckoo slasher violence of Dream Home — The Tenants plays more like artisan science fiction with slinking discomfort.

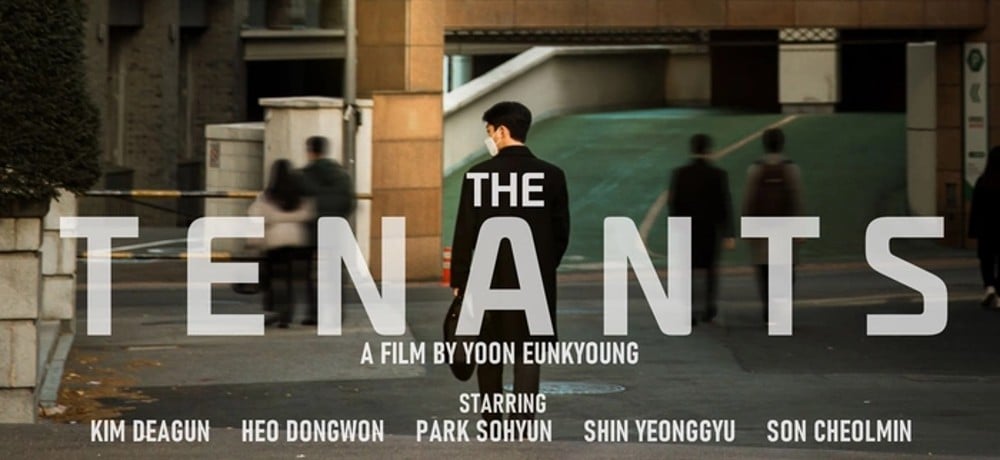

Shin-dong (Kim Dae-geon) is your typical slave to the grind. He crunches corporate numbers for Happy Meat, an artificial meat company that barely pays him enough to afford rent. That won’t matter much longer because Shin-dong’s child-aged landlord giddily reveals that his struggling tenant will soon be homeless due to building renovations. On a friend’s recommendation, Shin-dong devises a plan to lease out a portion of his unit under Wolwolse protections. Almost overnight, a mysterious couple — a dapper gentleman with dual feathers in his cap (Heo Dong-won) and his perpetually smiling, almost doll-like wife (Park So-Hyun) — moves into Shin-dong’s bathroom. Now he can’t get evicted, but that might not be the blessing Shin-dong presumes.

There’s a fragile thread connecting The Tenants and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, both protesting against classism through property markets. Shin-dong’s predicament is microcosmic; his flat has a few puny rooms, including his modest bathroom, converted into a two-person studio. Yoon walls tension within the absurd living arrangement, although most might reject describing The Tenants as “absurd” based on the film’s not-so-dystopian attributes. Shin-dong dreams of upgrading from an unsustainable middle-class Seoul lifestyle to “Sphere 2,” a utopia where citizens advance their careers and reap financial benefits. Yoon’s screenplay is devastatingly relatable, adding a few Retrofuturism tweaks to a universe of overworked, underpaid, and hopeless inhabitants that looks awfully familiar (in mirrors).

The Tenants steers away from in-your-face scares. What lingers are its midnight intrusions in the form of sleepwalking figures or symbolic nightmares. Shin-dong is tormented by a “Cheonjangse” renter, described as lower-class tenants who live in ceiling spaces for even less rent than his toilet-hugging roommates. This ominous concept of unfortunate souls residing in wall spaces becomes an uncomfortable unknown as Shin-dong’s property starts disappearing, but again, don’t expect exhilarating jolts. Imagery involving all-seeing eyes is but imaginary figments, where the story’s prevailing sensations of dread stem from parallels to reality. The suffocating themes about pounding keyboards after hours so a city can keep the wealthy atop their golden towers is despicably evergreen, especially in modern societies where inflation balloons while wages stagnate.

Shin-dong’s predicament is delicate, pinning survival on his ability to afford standard amenities. The film’s off-color details — surprising character ages and unchanging wardrobes — provoke an essence of uncanny simulations like Shin-dong’s trapped in limbo. The chosen monotone visuals accentuate overwhelming feelings of sadness. It’s not the most prolific commentary on back-breaking metropolitan existence, but complexity isn’t always necessary. Yoon cuts to the communal symptoms of crumbling empires where the rich get richer based on someone else’s grueling accomplishments, which is a total bummer. That’s the point. It’s the Japanese mumblecore answer to “Worksploitation” horror, as either a warning or recommendation.

Minimalism reigns supreme in The Tenants, a social satirization sparked by ire and dread in an era when business profitability is valued higher than employee appreciation. Yoon validates our routine exhaustion and chastises grind culture inside modest living quarters. Shin-dong is us, toiling away, watching prices skyrocket, clearing paychecks to fulfill payments so we can do it all again next month. It’s a stripped down execution, perhaps detrimentally so, but at the film’s core, Yoon finds bleakness in existence and tries to shake us from our existential ruts.

Movie Score: 3.5/5

![Brilliant Minds Season 1 Finale Review: [Spoiler’s] Return Throws Oliver’s World Out of Control Brilliant Minds Season 1 Finale Review: [Spoiler’s] Return Throws Oliver’s World Out of Control](https://cdn.tvfanatic.com/uploads/2025/01/Rushing-to-Save-the-Apartment-Victims-Brilliant-Minds-Season-1-Episode-12.jpg)