Trigger Warning: This story contains very graphic depictions of attempted suicide

I remember the first time I walked out to the bridge to kill myself. The year was 2007 and I was in college. I can recall everything about that night–the tingle of the winter air, the frozen snow crunching beneath my feet, and the feeling of darkness coursing in my veins. I couldn’t see anything but black. But I suppose everyone who struggles with suicidal ideation feels the same way. When I scrolled one evening for something to watch, I came across A Film for Friends, an obscure indie film that you can’t find anywhere except on YouTube. Directed by Radu Jude, the 2011 feature struck me across the chest with its pitch-perfect depiction of wanting to die but not wanting to die.

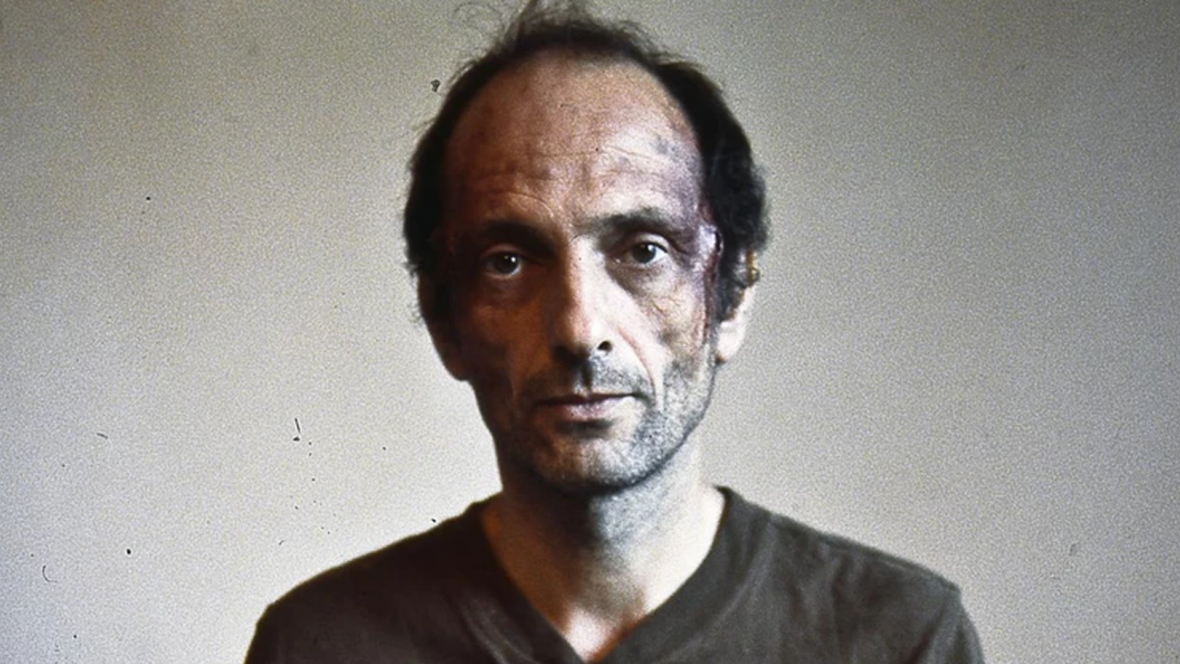

Gabriel Spahiu plays a man who stands at this crossroads. The film, shot “basically in one single shot,” according to various synopses online, opens with him filming a suicide note to his loved ones. He’s weary, beaten down, and exhausted from living. “The truth is I’m tired,” he tells the camera. For roughly 32 minutes, he agonizes over his life, labeling himself a “reject of society” and resigning himself to this allotment. The lengthy monologue, during which the man names specific people, including his son Bogdan, would fall apart in anyone else’s hands. But Spahiu delicately peels back the layers and displays a richness of raw, human emotion. He oscillates between unfiltered rage and devastating sadness.

While he determines not to blame anyone for the way his life has gone, he expresses a deep-chested loneliness. Despite assisting others as they need it, Spahiu’s character finds himself abandoned when he asks for help, carving out a hollow space where his heart should be. Lifeless and alone, the man sees himself with nowhere to turn and is stuck in a dark, cold place. He should feel alive, but all he feels is a thick blackness circling his shoulders. He wants so deeply to die and leave the world behind. All he hears inside his head is a malevolent voice echoing the same refrain: “I’m tired.”

When his monologue winds down, he takes a breath before grabbing a pistol from the table before him. He gives one last glance at the camera and shoots himself on the side of his head. His body flips over onto the floor. Jude stretches out the moment afterward and lingers on the scene. He leaves the camera static, and you slowly hear the man gurgling and crying somewhere off-camera. What transpires over the next 20 minutes or so is one of the most upsetting and disturbing things I’ve ever seen. Spahiu’s man writhes and screams, his blood soaking the sofa and the floor around him. He crawls to the apartment door and makes his way down the hallway, crawling and howling in pain.

Once again, Spahiu keeps the camera in place, making for an uncomfortable watch. You pray the scene cuts to black, but the clock only ticks by ever so slowly. Neighbors bustle in and out after bringing the man’s body back to the apartment. Still in agony, his screams grow less intense, and his breathing slows. When the paramedics show up, they get to work on giving him an IV and lifting him onto a stretcher. His voice fills the room, leaving a chill you just can’t shake. “I don’t want to die!” he howls in misery. They transport him from the room, leaving the viewer aghast and destroyed over what they’ve just witnessed. The camera hangs there before cutting to black…

“I don’t want to die” has stuck with me ever since I first watched A Film for Friends. Once the man realizes what he’s done, and that perhaps he’s meant to be alive, he feels regret pounding in his body. He didn’t want to actually die; he wanted to live and be seen. The tangled push-and-pull is hard to reconcile. You want to die, to finally be free of the weight of living—but you don’t want to die and miss out on everything great about living. It’s hard to fathom, but it’s real and honest.

Two years following the bridge incident, I took a bottle of Tylenol in the hope that I would be cast into darkness. I recall the moment and the moments after quite clearly. As I sat waiting for the pills to kick in, I heard my roommates come home, so I bolted out the side door. I ran. I ran as far as my body would carry me, which wasn’t very far as my body folded on itself. Then I sat down on the curb and retched until a blackness poured out of me. The sick bile shot like waves through my skin. At that moment, I knew I didn’t want to die. Bound in knots, I waited until it all passed. The thick tar flowed down the pavement, and I saw a light. Well, at least metaphorically, that what I wanted was to be needed by someone, anyone.

It took some time, but that was the last time I actively tried to kill myself. I continued to struggle with suicidal ideation for years after that. Therapy and medication helped tremendously in squashing those volatile thoughts that nearly cost me everything. And for that, I’m thankful. And I’m thankful for A Film for Friends and Radu Jude’s brutally raw depiction of attempted suicide. It’s never pretty and often violent, messy, and uncomfortable.

There’s been no film before or since that’s been so confrontational with its own material. It provokes you to think more deeply about people who walk along that precipice. A Film for Friends does an expert job of humanizing Gabriel Spahiu’s character. It pulls you into his world, and you feel every ounce of sorrow, pain, regret, and anger pouring out of his skin–until you begin to feel those same emotions. Spahiu’s performance is nothing short of a tour de force. It packs a punch, grabs you by the throat, and won’t let go.

We need more films like that.

Categorized:Editorials News