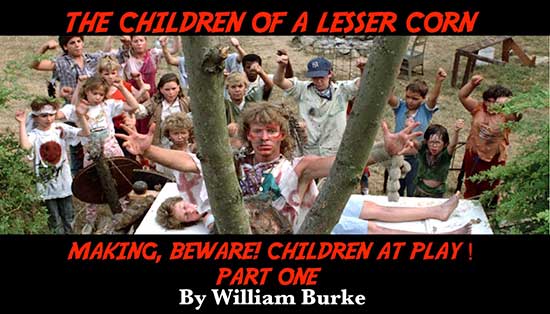

When I think back on the thirty plus movies and television shows I’ve worked on, one always stands out—a little gem entitled BEWARE CHILDREN AT PLAY. If the title doesn’t ring a bell, it’s that infamous movie where a dozen children are brutally slaughtered on camera. When Troma Films screened Beware’s trailer at the Cannes Film Festival it allegedly inspired outrage and mass walkouts. Personally, I’d chalk some of that up to Lloyd Kaufman’s ballyhoo, but it still sounds credible.

One quick note: Beware is often referred to as a Troma film, but technically it isn’t. It was picked up for distribution by the House of Kaufman several years after production. Troma released the film as a VHS and a barebones DVD with a low-end transfer. Just thought I’d clear that up.

Thankfully those cinephiles at Vinegar Syndrome have remastered Beware Children at Play for a Blu Ray release, adding copious special features to the package.

Some call Beware Children at Play, one of the worst films ever made, which I think is a stretch—I mean try sitting through Red Zone Cuba! It’s a bizarre and entertaining viewing experience that makes you ask, “What the F*** were they thinking?” And that’s what makes it so much fun. Looking back at Beware’s production offers a nice time capsule into making a no budget movie during the pre-digital, pre-CGI age; back when films were shot on film, movie blood was sticky and the boundaries of good taste were only there to be trampled over.

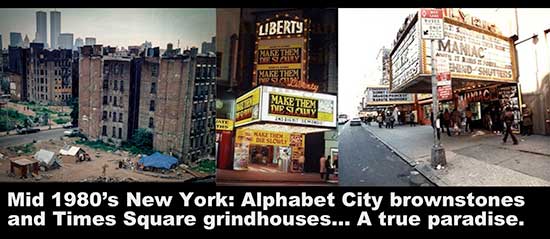

My involvement stemmed from a lifelong love for low budget horror movies. As a kid I devoured magazines like Famous Monsters. During my time in the military, I discovered Fangoria, a magazine chock full of tales of New York indie horror films like Basket Case. Clearly, that the place to be. Upon leaving the military I moved into a fifth-floor walk-up in Manhattan’s rough and tumble Alphabet City. I gravitated to Times Square grindhouses, watching classics like Zombie and Maniac on the big screen. Sitting in a theater full of day-release mental patients, drug dealers and knife wielding crack heads adds an extra dimension to titles like Make Them Die Slowly. In 1984, New York was truly a land of wonders… as long as you didn’t get stabbed on the F-Train.

Fast forward two years. I’d just finished broadcast engineering school, and wrangled a video production gig at the United Nations. A chance meeting with effects artist John Dods (The Deadly Spawn) Ied to my spending weekends in Rye, New York, puppeteering on Spookies (originally Twisted Souls). That film’s director urged me to see Mic Cribben and Ellen Wedner—a husband and wife duo making a horror film titled Goblins (which later became Beware Children at Play). Mic owned his own 35mm Arriflex BL1 package, along with a Nagra recorder and a Steenbeck editing table—the building blocks of making a film. What they didn’t have was money, but they weren’t letting that stop them.

After shrewdly negotiating my salary up to zero, I was hired as Production Manager, despite having little clue what that entailed. In real life, the production manager is responsible for keeping the film on budget, which was easy on Beware, as there wasn’t a budget to begin with. Some of my work involved finding other crewmembers to work for free. In return for their labors, they would get free rentals on Mic’s equipment, so it wasn’t like I was recruiting for Scientology.

You might be picturing Mic and Ellen as sleazy people out to produce a cheap shock film. Well, during my tenure in New York, I met grindhouse stalwarts like Joel Reed (Bloodsucking Freaks) who really lived up to their seedy reputations. Mic and Ellen were quite the opposite. She was a charming, whip smart woman who did well in real estate. Mic was an instantly likeable guy with hilarious, if politically incorrect, film set stories. He’d also been an actor, appearing in films like 1981’s slasher movie Nightmare. He was also the unit manager and sound mixer on that low budget opus.

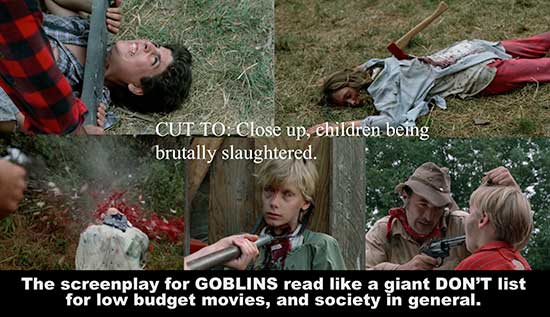

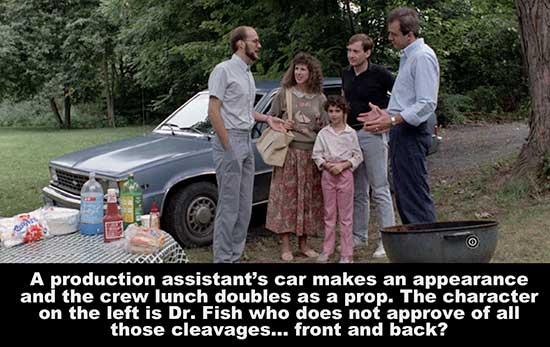

Reading the script was a real eye opener. I’d been expecting a slasher film, which were still the go-to cheap movie genre. But this film had dozens of child actors along with tons of extras playing redneck townsfolk. Even more jaw dropping was the movie’s finale where all of the children are slaughtered in a Mÿ Lai style massacre. It read like a checklist of everything not to attempt on a micro budget. It was also the first, and last time I heard the term ‘cleavages,’ used. It’s mentioned twice. Dr Fish actually says, “cleavages, front and back.” What does that even mean?

An investor had bestowed Mic and Ellen with a cash budget of around $25,000, which wasn’t much, even by 1980’s standards. In truth it amounted to less than an equal amount of cash today, because we were shooting on 35mm film. In those pre digital days the bulk of an indie film’s budget went to film stock and processing. To shoot their movies, impoverished filmmakers resorted to what you might call used film, more commonly known as short ends.

Short ends were what remained in a film magazine after a day’s shooting on bigger movies. These ‘beaks and claws’ were re-canned by the camera department. There might be as little as 100 feet of film rattling around in a can. A thousand-foot roll of 35mm film only runs about ten minutes, so you’re not looking at much camera time on that short end. Plus, the short ends were never tested to see if the previous camera department had re-canned it properly. This was dumpster diving meets Russian Roulette.

FUN FACT: Years later I started a side hustle by buying thousands of feet of sealed rebought film and storing it in my refrigerator next to the beer and eggs. On weekends I’d get panicked calls from music video producers who’d run out of film. I charged a hefty markup for rescuing their production, but I threw in free delivery.

Using such short rolls created lots of downtime while magazines were reloaded with another meager ration of film. That can be a drag when you’re dealing with child actors with a limited attention span. I recall one night when the rolls were so short that we couldn’t finish a one-minute scene without rolling out.

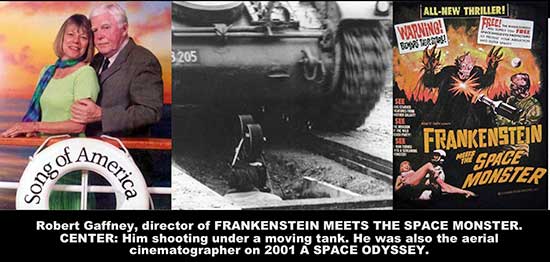

To minimize downtime Mic would borrow magazines from NY production company Ross Gaffney Inc. Picking up those magazines gave me an excuse to meet the company’s owner, Robert Gaffney, director of 1965’s Frankenstein vs the Space Monster. I think he was flattered, if slightly bewildered at having some young film geek fawning over him. Wow, I really walked among giants!

A mix of film brands only added to the fun, as each had a distinctly different look. The finished film is a melange of Kodak’s classic Hollywood look, Fuji’s punchy Tokyo-pop color and AGFA’s somber German sturm und drang. I don’t think Mic used different brands in the same scene, but during night scenes you can see the film grain and color shifting between connecting scenes.

The film was processed by Studio Film Labs, who were eager to make deals—probably because the porn industries transition from shooting on film to video was crippling their bottom line. Mic and Ellen saved additional money by having the footage reduction printed from 35mm to 16mm. George Romero used the same money saving tactic on Dawn of the Dead.

The production was shot entirely on weekends in the wilds of New Jersey. Hauling twenty or so non-driving Manhattanites to the location was always a challenge. Some production assistants were hired because they owned cars that we used to transport the actors. Crew members usually just sat on equipment cases in the back of the cargo van. Seat belt and open container laws were routinely ignored on the trips back to NYC. Mic’s van probably reeked of Old Milwaukee beer and ditch weed until the day it died. Good times… good times.

And if you’re looking for a thrilling read, that’s a 100% child murder free, check out my new novel DOMINANT SPECIES, published by those masters of monster mayhem at Severed Press.